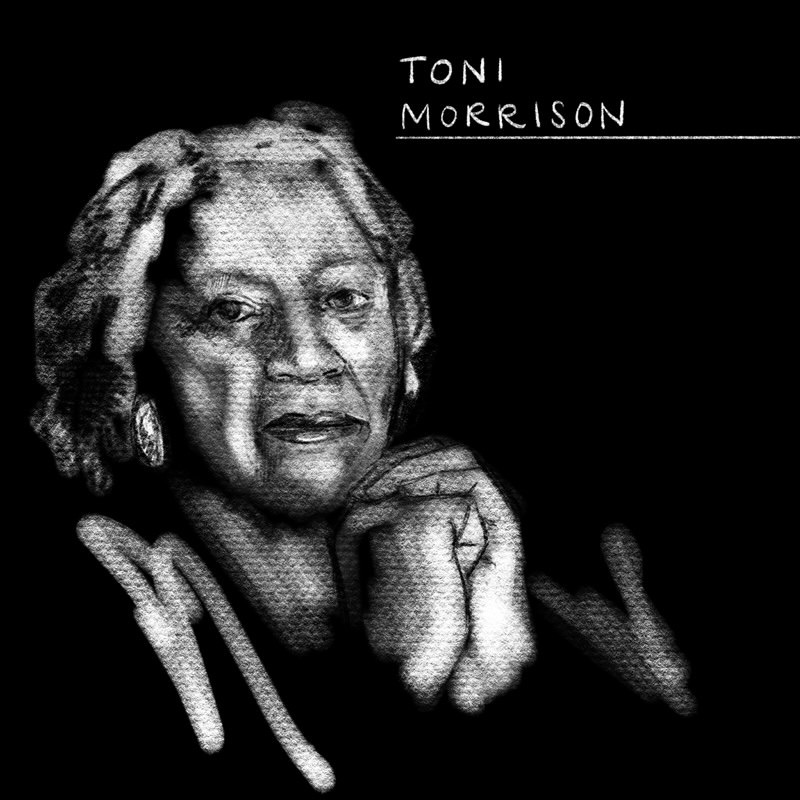

I saw the below quote posted on @__nitch today and since @reginaaustinart had already made me this truly transcendent Toni Morrison, it felt fitting to share them on day two of #womenshistorymonth

“I am staring out the window in an extremely dark mood, feeling helpless. Than a friend, a fellow artist, calls…he asks, “How are you?” And instead of “Oh, fine…and you?” I blurt out the truth: “Not well. Not only am I depressed, I can’t seem to work, to write; it’s as though I am paralyzed, unable to write anything…I’ve never felt this way before…” I am about to explain with further detail when he interrupts, shouting: “No! No, no, no! This is precisely the time when artists go to work…not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job.” I feel foolish the rest of the morning, especially when I recalled the artists who had done their work in gulags, prison cells, hospital beds; who did their work while hounded, exiled, reviled, pilloried. And those who were executed…This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”